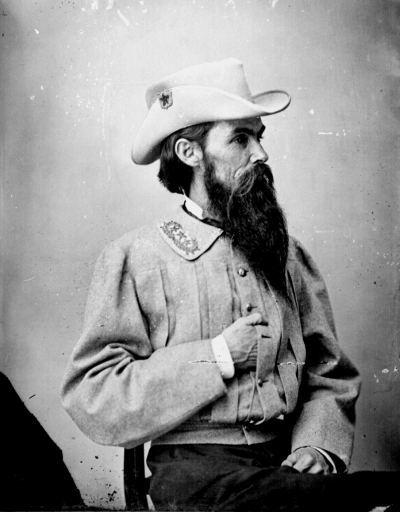

Confederate officer William Pegram

After weeks of preparation, Union forces detonated a mine under the Confederate lines outside Petersburg, Virginia, on July 30, 1864. Union infantry then launched an assault toward the breach in the Rebel line in hopes of exploiting the confusion the explosion caused. Much of the attacking force, comprised in part of African-American troops, soon became bogged down in the crater caused by the blast; the Confederates rallied, formed around the crater, and inflicted heavy losses on the trapped Union soldiers—including killing many of the African-American troops who tried to surrender.One of the Confederates present to witness the bloody fight was Colonel William “Willie” Pegram, a 23-year-old artillerist in the Army of Northern Virginia. Two days after the decisive Confederate victory, Pegram wrote his sister to describe that he had seen:

Petersburg, Aug: 1st 1864

My dear Jenny

I believe that you owe me a letter, but of this I am not certain; and even if I was, it would not prevent my writing to you, as I wish to set you a good example as a correspondent.

I suppose you all have gotten, before this, a correct account of the affair on Saturday. It was an exceedingly brilliant one for us.

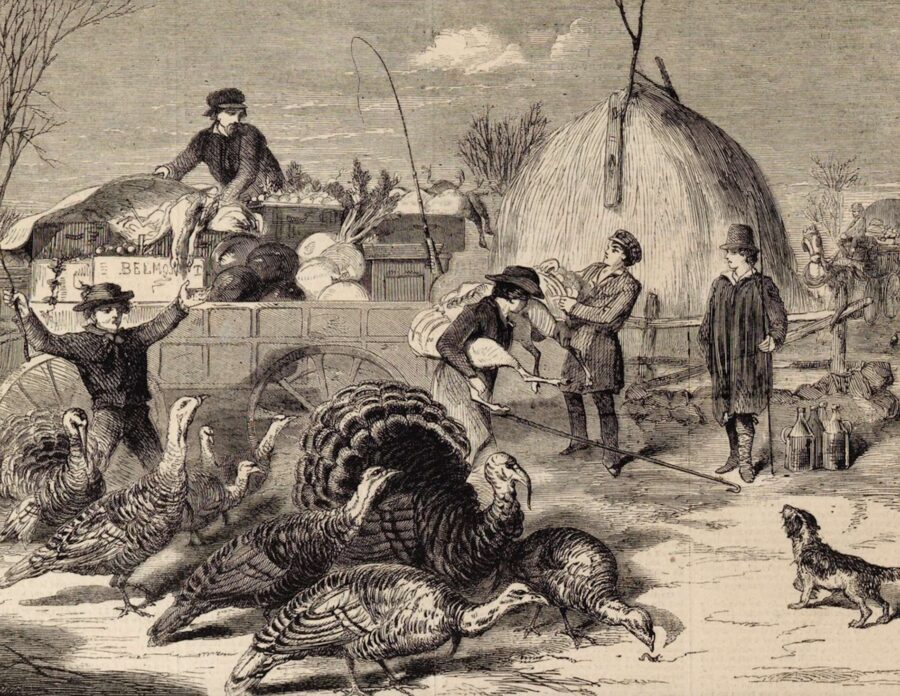

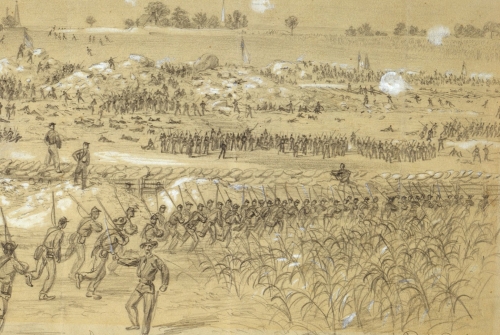

Union troops charge toward the crater created in the Confederate lines outside Petersburg in this sketch by Alfred Waud.

The enemy avoided our mine, & ran theirs under Cousin Dick’s Batty. They blew it up about daylight, & taking advantage of the temporary confusion & demoralization of our troops at that point, rushed a large body of whites & blacks into the breach. This turned out much worse for them in the end. The ever ready [Brigadier General William] Mahone was carried down to retake the line with his fine troops, which he did, with comparatively small loss to himself, & great loss to the enemy. I never saw such a sight as I saw on that portion of the line—for a good distance in the trenches, the Yankees, white & black, principally the latter, were piled two or three or four deep. A few of our men were wounded by the negroes, which exasperated them very much. There were hardly less than six hundred dead—four hundred of whom were negroes. As soon as we got upon them, they threw down their arms to surrender, but were not allowed to do so. Every bomb proof I saw, had one or two dead negroes in it, who had skulked out of the fight, & been found & killed by our men. This was perfectly right, as a matter of policy. I think over two hundred negroes got into our lines, by surrendering & running in, along with the whites, while the fighting was going on. I don’t believe that much over half of these ever reached the rear. You could see them lying dead all along the route to the rear. While there was a temporary lull in the fighting, after we had recaptured the first portion of the line, & before we recaptured the second, I was down there, & saw a fight between a negro & one of our men in the trench. I suppose that the Confederate told the negro he was going to kill him, after he had surrendered. This made the negro desperate, & he grabbed up a musket, & they fought quite desperately for a little while with bayonets, until a bystander shot the negro dead.

Confederate general William Mahone

It seems cruel to murder them in cold blood, but I think the men who did it had very good cause for doing so. Gen. Mahone told me of one man who had a bayonet run through his cheek, which instead of making him throw down his musket & run to the rear, as men usually do when they are wounded, exasperated him so much that he killed the negro, although in that condition. I have always said that I wished the enemy would bring some negroes against this army. I am convinced, since Saturday’s fight, that it has a splendid effect on our men.

I did not fire any guns on Saturday, but got some in position, where they were exposed to some shelling & musketry. My hat was struck by a Minie ball just over the place I was wounded at Sharpsburg, which was quite a singular coincidence. I saw Cousin Dick Pegram after the fight. Fortunately, he had been relieved, & was not in the trenches when the mine was sprung.

On the whole, Saturday was, through the merciful kindness of an all & ever-merciful God, a very brilliant day to us. The enemy’s loss was, at the lowest figures, three to our one—but the moral effect to our arms was very great. For it shews that he cannot blow us out of our works; or, at least, that he cannot hold a breach after making it. Saturday’s fight shewed also the superiority of veterans to new troops—i.e. of Lee’s to [General P.G.T.] Beauregard’s troops. They had to take Mahone’s Division from this portion of the line, to that point, near the centre, to retake & reestablish the line, because those troops failed, although, as I was told by one of Beauregard’s staff, they had a very fine opportunity for doing so immediately after the explosion….

Is there any news from Atlanta? I am looking daily for its fall. If Maj Bradford is still with you, give him my love—& Ask him why he does not run over. Excuse haste. Your devoted brother

W. J. Pegram

Union forces would finally break through the Confederate defenses at Petersburg on April 2, 1865. The previous day, Pegram suffered a mortal wound at the Battle of Five Forks. He died roughly three months shy of his 24th birthday.